Offshore Wind-farms – particularly their underwater cables – are especially vulnerable to being sabotaged by a rogue state with a large submarine fleet – no prizes for guessing which..!

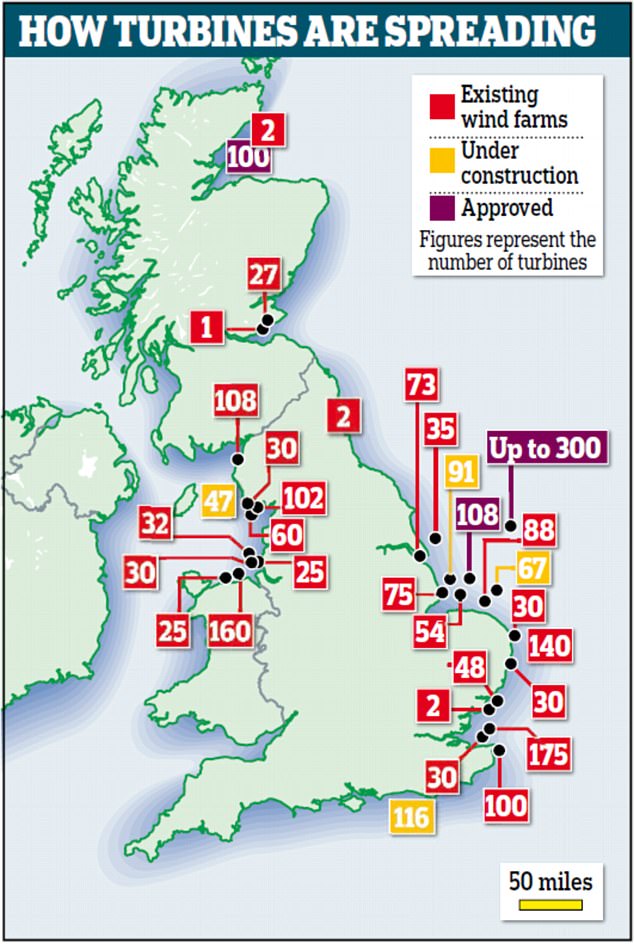

David Mackay, author of “Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air”, has speculated on the number of onshore wind turbines Britain would need to slake its energy thirst….

What fraction of the country can we really imagine covering with windmills? If we covered the windiest 10% of the country with windmills (delivering 2 W/m2), we would be able to generate 20 kWh/d per person, which is half of the power used by driving an average fossil-fuel car 50 km per day. Britain’s onshore wind energy resource may be “huge,” but it’s not as huge as our huge demand for power.

SIZE MATTERS

With wind turbines bigger really is better. And they are getting bigger all the time – the biggest offshore ones have blades over 100m long and are rated at up to 15MW, sufficient (or so they like to claim) to “power 5000 houses”. But that would be its MAXIMUM output under the most favourable conditions. Unlike with a coal-fired or a nuclear reactor which can deliver peak output whenever it is called upon to do so, a wind-turbine can only produce its maximum rating under ideal wind conditions. Manufacturers claim their turbines generate an average output of “at least 30% of capacity”, but this should be taken with a pinch of salt.

[stextbox id=’info’]Britain’s best-known wind turbine, located next to Junction 11 of the M4 at Reading, consists of a 85m tower with 33m blades and a “2MW” generator. Between 2005 and 2010 it received £600,000 in public subsidies and worked at just 17% of its capacity. So its average output was just 0.35MW, compared with its theoretical output of 2MW. This may be an extreme example because, judging by its proximity to some large buildings, and the turbulence that they would create, it is certainly not located in an ideal wind-catching position. Its main purpose appears to be that of a promotional gimmick for the Business Park within which it is located.

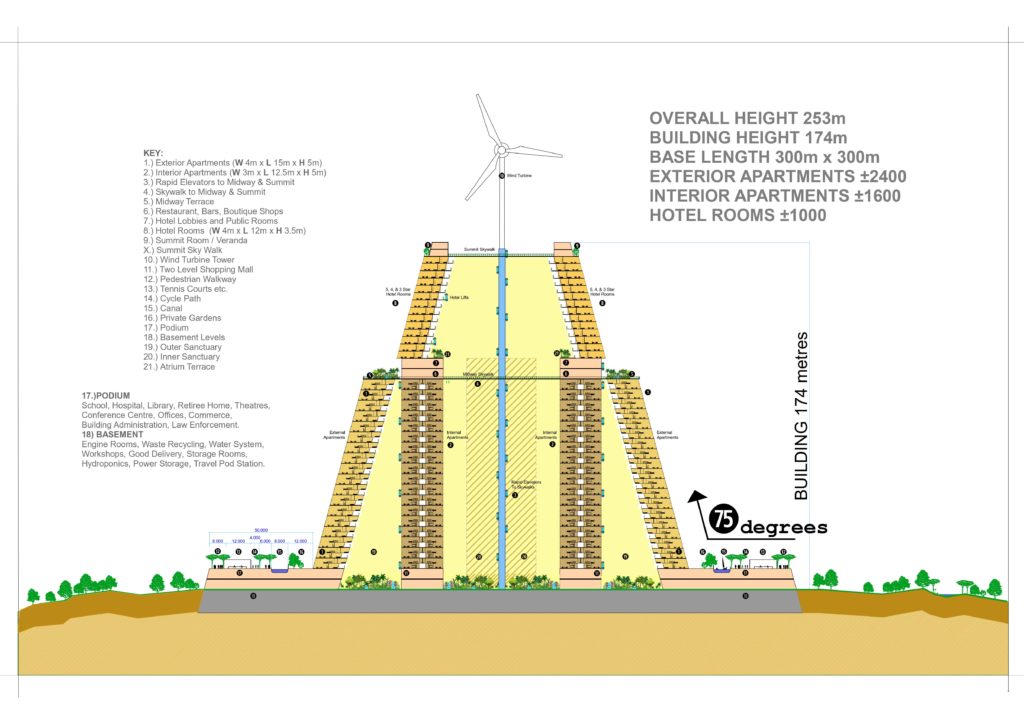

OΔCity modules could be wind-turbine platforms

My original idea was to place a dozen or so smaller wind-turbines along the edge of the podium wall, but critics soon pointed out that the building would block the wind, thus leaving half of them in the wind’s shadow. Then a friend of a friend called Baldrick came up with what he called a “cunning plan” – put them on a rail track so that they could be moved to face wherever the wind was coming from. Of course such top-heavy towers would need to be secured to a very sturdy wheeled base, like railway gun-carriages.

Realising that Baldrick was an idiot, I came up with the idea of a “building-integrated” turbine.

Building-integrated wind turbines offer many advantages

-

Power source is on-site, so no transmission loss or ugly pylons.

-

Turbine height is raised clear of obstructions, therefore much more efficient.

-

The additional tower height is effectively free, since the first 180m of the tower is already in place.

-

Each OA-City mounted turbine would be optimally-spaced at about 500m from its nearest neighbour,

-

Onshore wind-farms are generally considered an eyesore – I don’t think the same could (or will) be said about building-integrated turbines.

-

They also render the land on which they sit useless for residential purposes.

-

OA-City residents would benefit directly, so no NIMBY attitude

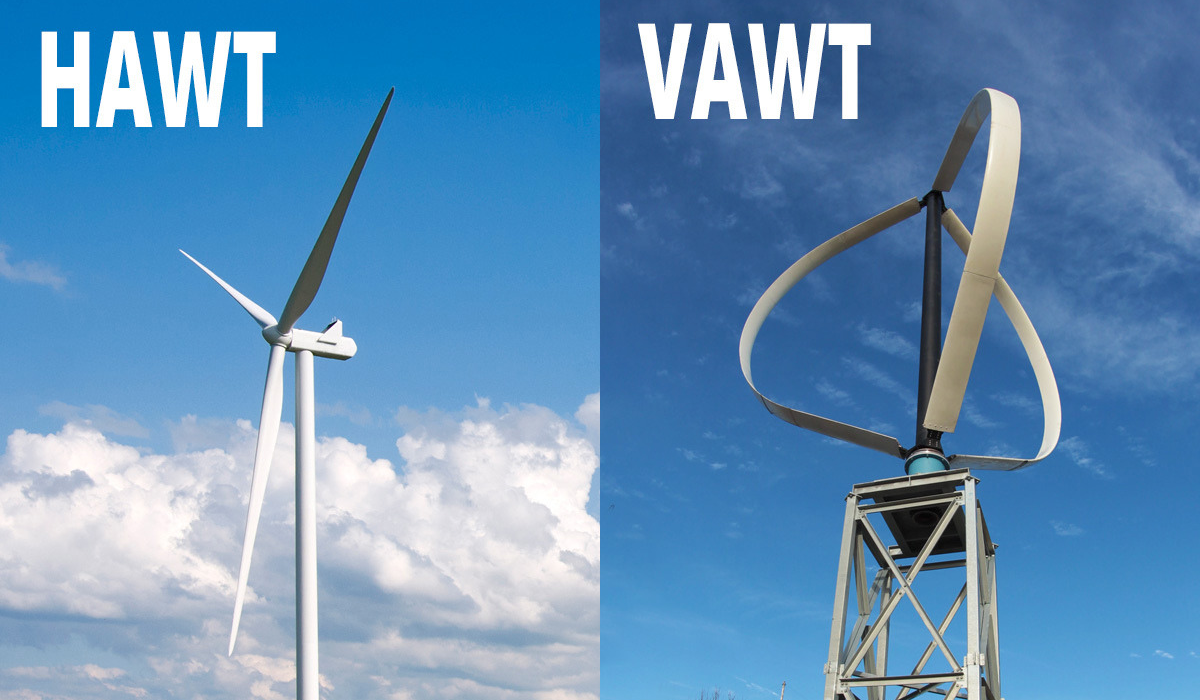

All commercial wind-farms use the Horizontal Axis (HAWT) type, with the now familiar huge propeller-shaped blades. Vertical Axis (VAWT) have only been used in small-scale applications but, if large ones can be shown to be as efficient as HAWT, as claimed by some, then the VAWT type – utilising either paddles, scoops or a helical rotor – may be the future.